Birthright Citizenship and the Populist Chainsaw

Other nations reformed birthright laws through process. In the U.S., it became political theater.

Populists love big swings. Headlines. Shockwaves. The bigger the gesture, the more powerful it looks — no matter how constitutionally reckless or legally hollow it may be.

That’s exactly what we’re seeing in the latest surge of calls to end birthright citizenship in the United States. The idea isn’t new, but the tone is different now: it’s not being debated as a legal or constitutional question. It’s being wielded like a political weapon. Again.

This fits the same populist pattern I explored in a recent piece, “The Real Threat Isn’t Left or Right — It’s Populism.” Populists don’t care which side of the aisle they’re on — they care about bypassing process to deliver outrage-driven wins.

A Real Debate, Hijacked by Optics

There are valid questions to ask about birthright citizenship in the 21st century. Many peer nations — like the UK, Australia, and New Zealand — have significantly restricted automatic birthright citizenship in recent decades. Others, like Germany and France, apply conditions that limit or delay citizenship based on residency or parental citizenship status. They did it through legislation or reform, not outrage. They did it slowly, and in response to very different immigration dynamics.

In the U.S., however, the issue is uniquely constitutional. The 14th Amendment was designed after the Civil War to ensure that former slaves and their descendants could never be denied citizenship. Its language is broad and powerful: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States… are citizens of the United States.” Any change to that is not a policy tweak. It’s a constitutional shift — and that means an amendment.

But that’s not how populists approach problems. They don’t govern. They break.

Why Amendments Don’t Appeal to Populists

Real change — constitutional change — takes time. It requires consensus. It involves deliberation, persuasion, and a belief in the process. Populism, on the other hand, is fueled by urgency, optics, and the illusion of decisive action.

So instead of engaging in the difficult, democratic work of amending the Constitution (which they’re free to try), populist politicians float executive orders or vague legal reinterpretations. Not because it will work — but because it sounds bold. It creates friction. It “owns” the opposition. And it gives the appearance of power without the burden of responsibility.

In other words: optics matter more than outcome.

And if it fails? Even better. Populists thrive on losing battles they were never meant to win. It gives them a grievance. It feeds the narrative: “The elites stopped us.”

Are We Ready to Revisit Birthright Citizenship?

Maybe. But if we are, it has to happen the right way.

We should be willing to ask whether the 14th Amendment’s birthright clause still makes sense in today’s world. Immigration looks very different in 2025 than it did in 1868. But that conversation must happen in Congress, in public debate, and ultimately through a constitutional process. Not in a campaign rally. Not in a tweet. Not in a courtroom shortcut.

If the goal is to fix something, we have the tools. But populists don’t want to fix systems — they want to smash them for applause.

Populism Isn’t Just Angry. It’s Lazy.

Real leadership means having the patience to work within the framework you swore to uphold. Populism, by contrast, is impatient by design. It’s not interested in governance — it’s interested in theater. And birthright citizenship, like so many other serious issues, has become just another stage prop.

If we’re going to change something as foundational as who gets to be American, we should do it the American way: by amending the Constitution — not gutting it on impulse.

Because when populism drives the conversation, the outcome isn’t reform. It’s wreckage dressed up as revolution.

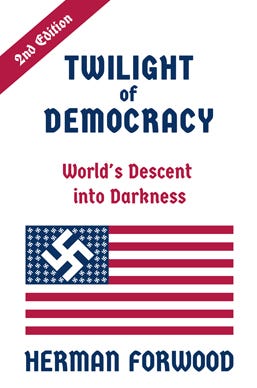

This is exactly the kind of shortcut logic I explored in “Twilight of Democracy: World’s Descent into Darkness.” In the world I imagined, where populism didn’t just surge but won, the legal framework didn’t bend overnight — it eroded slowly, often under the guise of fixing something “obvious.” The people wanted fast answers. The leaders wanted applause. And the Constitution? It was just in the way.

Birthright citizenship may or may not deserve reform. But in a populist political culture, the question isn’t how we change something. It’s how fast we can look like we changed it.

That’s the danger.

In “Twilight of Democracy,” I tried to show what happens when the institutions meant to protect us are treated like obstacles instead of foundations. When leaders stop making real changes through real channels — and instead reach for power through optics, rage, and performance.

If populism keeps taking the lead, we won’t just lose the debates. We’ll lose the structure that lets us have them.

I agree all along. But it is fascinating how “birthright citizenship” could be search-&-replaced in your article with “gun control” and it all still holds up perfectly. The correspondence is striking.